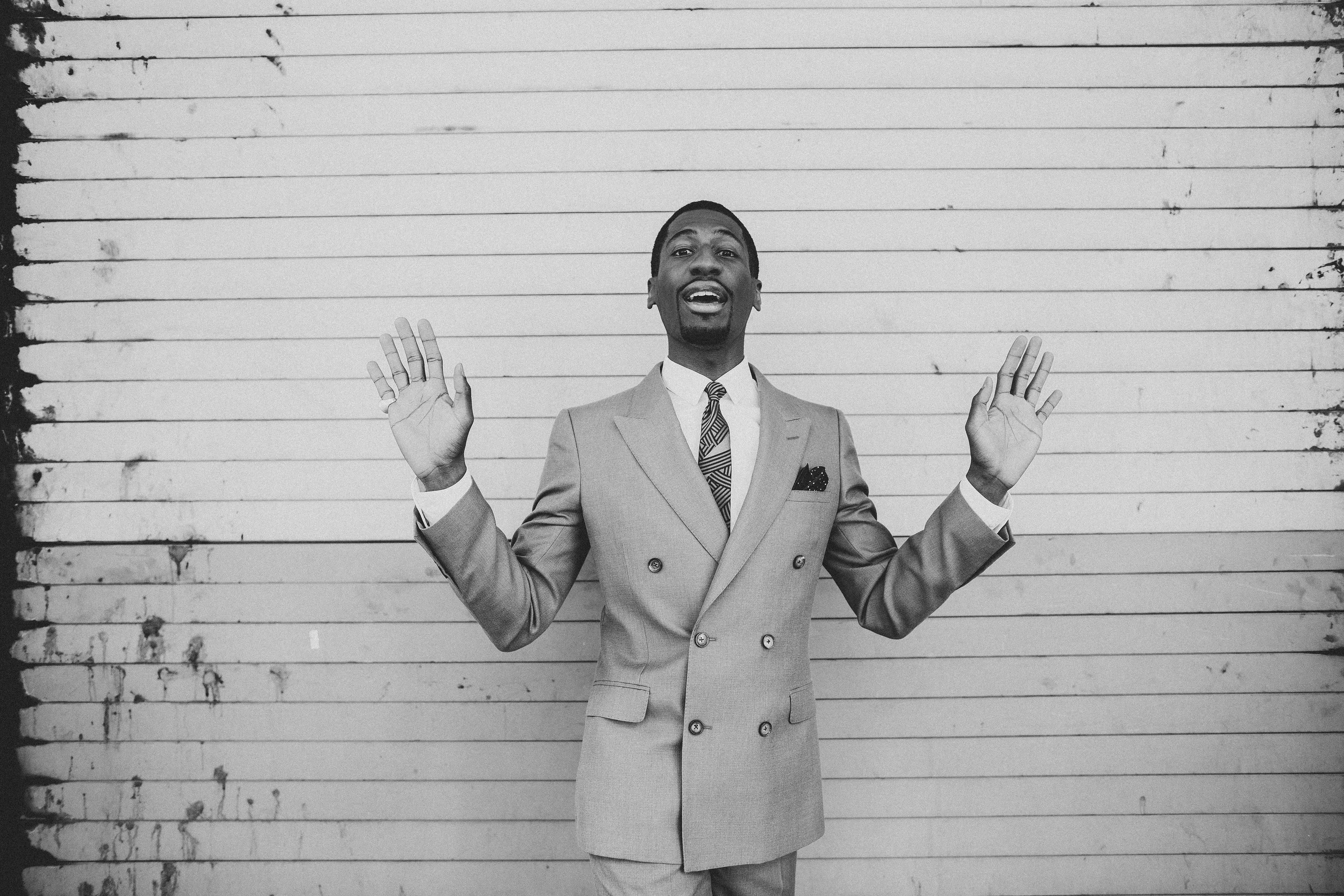

By JON BATISTE

NEW YORK TIMES

OCT. 27, 2017

Jon Batiste, band director for “The Late Show With Stephen Colbert,” plays the basic melody of “When the Saints Go Marching In,” followed by a Fats Domino-style interpretation of it.

My first exposure to rock ’n’ roll came from watching mostly white bands like Nirvana, Korn and Limp Bizkit perform angsty songs on MTV. I bought some of

eir albums, but the genre didn’t really resonate with me until I learned that black people could be rock ’n’ roll artists too. None had as great an influence on me as Fats Domino, one of the biggest stars of the early rock ’n’ roll era, who died on Tuesday in Harvey, La.

I was raised in a musical household in New Orleans. I played the drums and piano as a child, and my dad played bass. He and his bandmates encouraged me to study the history of rock ’n’ roll, not dismiss it. In one of my weekly runs to Blockbuster’s used CDs section, I found a Led Zeppelin CD, which eventually led me to Jimi Hendrix. He was the first black person I learned about who played rock ’n’ roll — a term I thought was fixed but whose meaning kept expanding.

Around then, I began to play gigs with bands that would occasionally cover Mr. Hendrix’s songs, and it was powerful to watch the audience react. I wanted to be able to tap into that kind of energy too, but also to balance it with something else I couldn’t quite identify yet.

Around 1998, when I was 12 years old, I sat in on one of my father’s gigs and first heard “Blueberry Hill” by Fats Domino. The song seemed deeply familiar; it was almost as if it was otherworldly, floating somewhere in the ether. I had never heard such a percussive piano section. Folks of various ages and races got up to dance and sing along in a joyous communal outburst.

In this yearslong study of rock ’n’ roll, I had finally arrived at the beginning: Fats Domino.

While jazz was born in New Orleans in the early 1900s, and the city played a significant role in shaping rock ’n’ roll, Antoine Domino, known as Fats, was one of the few musicians who bridged those two genres. He was influenced by the first and laid the groundwork for the second.

The world began to take notice of Mr. Domino’s music in 1949 with the release of “The Fat Man” by Imperial Records. Through the 1950s and early ’60s, he gained enormous fame, selling 65 million singles, with 23 gold records. Even Elvis Presley said Mr. Domino had influenced him.

For years, the famed disc jockey and concert promoter Alan Freed presented Mr. Domino’s “race records” on the radio to growing audiences at home and overseas. But over time, the music industry marketed black rock ’n’ rollers like Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, Little Richard and others in a way that all but erased their legacy from what millennials like me had considered rock ’n’ roll.

Maybe that explains why it was only after I enrolled at Juilliard when I was 17 years old and really studied Mr. Domino’s catalog that I fully grasped the significance of the fact that an African-American man, born in the Jim Crow South, was a founder of a mostly white musical movement.

Mr. Domino pioneered a rollicking style of piano playing. His approach brought together extremes: It was both straight and swung (a defining trait of rock ’n’ roll), percussive and melodic, aggressive and sweet. The push and pull created a feeling that was both sophisticated and accessible.

Rhythmically, his style embodied the spirit of New Orleans. He brought together second-line parade music and boogie-woogie piano, which was basically brothel music. He could also write and reinterpret music that was not traditionally performed by black artists and filter it through his sensibility. It was colloquial. It was irresistible.

When I was growing up, most of what I heard about Mr. Domino was that he was friendly and a sharp dresser. But my father told me a story about Mr. Domino during a sound check that shows he was a musician of the highest order. Mr. Domino was practicing his signature piano style while talking to a reporter. With the discipline of an army general, he continued playing until he was satisfied, cordially shooing the interviewer away so that he could focus.

I’ll also remember Mr. Domino’s humility. He never believed the hype about him. And he was immune to taking himself too seriously. I’ve even heard musicians talk about how he would bring his pots and pans on tour and cook red beans and rice for the crew.

My colleagues and I on “The Late Show With Stephen Colbert” often joke about people in the “establishment.” To us, they represent almost the antithesis of progress and creativity. But when it comes to music, the “establishment” includes artists like Fats Domino.

Fats Domino passed away this week, knowing full well that he holds a rare title: founder of both the jazz and the early rock ’n’ roll establishments. As we celebrate his achievements, we ought to remember the real roots of rock ’n’ roll, our national music.